�����������

The Corvus

And Its

Decisive Role in the First War Between Rome and Carthage

����������� Romans are not often

remembered as great artists of the ancient world.� Hellenophiles are apt to dismiss them as nothing more than mere

copycat conquerors.� But the Romans

excelled in the art that has brought man from the plains of Africa to the Moon

and back again:� problemsolving.� It was the proficiency at this art that

allowed the Rome to rise from a small Etruscan-rule settlement on the Tiber to

become master of Mediterranean civilization in its thousand year wax.� If art is turning an idea into a thing of

beauty, then surely the city-planners, generals, aqueduct builders, and other

Roman engineers where among the greatest artists of the ancient world.

����������� After

the conquest of the Italian peninsula was completed in mid third century BC,

Rome found itself up against its most formidable enemy ever: the

Phoenicians.� The Phoenicians are a

great example of a people who never gave up, no matter how many times they

where defeated.� History first meets

them as the Philistines, idolatrous Baal-worshiping inhabitants of Canaan, the

land Yahweh had promised to the wandering Hebrews. The Phoenician Goliath was,

of course, bested by David and pushed to the coast, where the staunchly guarded

ports that helped Phoenician traders dominate the Mediterranean were

located.� The example of this feat was

to be later repeated by another group out of the Arabian desert claiming

descendance from Abraham under their general Mohammed.

Following their early losses

to the Hebrews, the Phoenicians were given a bit of respite in which to develop

their profitable sea trade as the Assyrians and then the Babylonians

successively conquered there troublesome neighbor to the East.� Finally pulled under the sway of the

Persians, the Phoenicians were nevertheless allowed to continue much as

before.� Of course, the Persian emperor

Xerxes could not resist the temptation of conquering Greece, and his failure

weakened the great eastern empire so much that the next generation saw Greece

returning the favor.� While conquering

Asia, the Greeks took their turn bashing the followers of Baal as Alexander the

Great marched his army all over the eastern Mediterranean world and beyond in

the 4th century BC.� The

Phoenician capital Tyre, the siege of which gave Alexander a run for his money,

eventually capitulated in 332 BC.�

Thereafter, Phoenician operations were based out of their largest city

west of Alexander�s conquests: Carthage, located on the north coast of

Africa.�

From Carthage, the

Phoenicians ruled over trade in the lucrative western Mediterranean and

eventually came to hold sway over North Africa, Spain, and Sicily.� The only obstacle to the complete domination

of the western Mediterranean was Rome, where they called the Phoenicians

Punica.� If bets were taken in the early

3rd century BC on who would win this conflict for domination of the

western half of the civilized world, the Phoenicians would have been the clear

favorite.� However, this was not to

be.� The Phoenicians would not rise to

dominate the world until Septimius Severus founded the dynasty that bears his

name on the Roman imperial throne in the 2nd century AD.� And then despite his ancestry and continued

worship of a form of Baal, Severus was a Roman general; a commander of Legions

who spoke Latin, even if it was with a provincial�s accent.� The Fates never truly cast their favor with

the Phoenicians.� Nevertheless, the

three Punic Wars fought between Rome and Carthage were the fire that forged the

military might of Rome.

����������� It

is upon their first meeting that we now focus.�

Roman experience up to this point was mostly in subjugating tribes and

cities in territories adjacent to Roman territory.� They had mastered the art of land warfare in the form of the

Legion.� Only the upper half of Roman

society served in this body, and then with a rank corresponding to the

individual�s social standing.� These men

had the most to gain if Rome won its wars, and the most to lose if Rome

lost.� Such a fighting force was without

equal in the ancient world, and this is perhaps why Rome was destined to

dominate it.� Most armies of the day

were mercenary in character, with plunder to gain in victory but nothing to

lose but their lives in defeat.

����������� The

Romans, however, did not need a navy to conquer the lands of Italy, and had not

really developed any great trade enterprises either.� The Roman ideal of the farmer working his land led them to

prohibit mercantile activities amongst the wealthier classes of Rome.� Thus, while under Roman domain the conquered

Etruscans of northern Italy traded from their port at Hadria and the conquered

Greeks of southern Italy from their ports at Sybaris, Tarentum, and Croton, the

Romans discouraged such activities amongst themselves.� Hence, their knowledge of shipbuilding and

seamanship was next to nonexistant.�

However, upon confronting the naval might of Carthage, Rome realized that

this deficiency must be quickly remedied if she was to survive.

����������� Thus

the Romans took up the task of putting a legion on the sea.� Off the coast of Italy, a local had

propitiously found the wreck of a Carthaginian quinquereme, one of their

principle ships of war.� The Roman

Senate immediately ordered 100 to be built from this model by the experienced

shipwrights in the newly conquered Greek cities of southern Italy.� Soon the newly built Roman fleet was sailing

the mild waters of the Mediterranean Sea, but the problem still existed: how to

get the legionnaires off of the Roman ships and onto that of their enemies, the

Carthaginians.� The solution to this

problem would give the Romans an advantage at sea equal to the proven

effectiveness of the legions on land.�

In solving this quandary, the Romans took the art of problemsolving to a new level.� Singlemindedly ignoring the advice of their naval advisors in conquered Italy, the Romans attempted in no way to learn about the art of war upon the sea.� They saw fit to map a problem they knew how to solve, that of a land battle, on to one they had not yet encountered, that of a battle at sea.� In a land battle, it is the troops that make the difference and fight the war.� So Rome figured the same ought to be true at sea.� Indeed, what are ships but big siege engines built to conduct troops into the camp of the enemy.� And if the Carthaginian ships were the enemy camps, the Corvus was the way to get there.

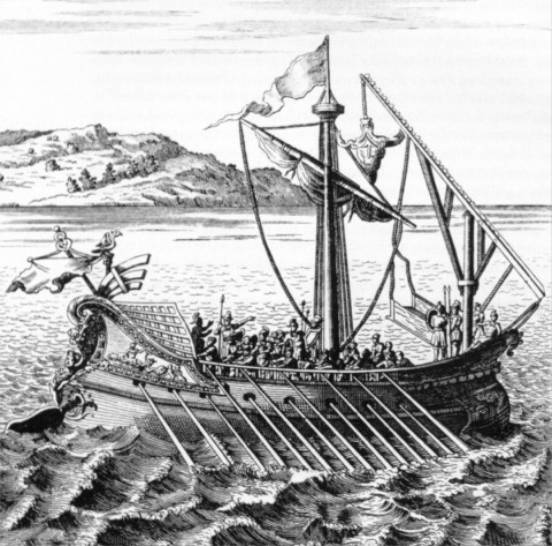

����������� Unfortunately, history has not afforded us the luxury of a surviving corvus to study, so we must instead rely upon accounts.� Polybius, who was alive to interview veterans of the second Punic War, is the best of these sources.� By virtue of its name, corvus, the Latin word for raven, we can surmise that it was probably dark in color if not black, and shaped like a bird.� Consisting of a massive object attached to a gangplank, we have but little information on how exactly the corvus was deployed.� Polybius relates that the corvus, by the force of its fall onto an enemy ship, linked the ships by piercing the deck much like a grappling hook. �Since it was necessary for the corvus to fall upon the deck of another ship in battle, it must have been either held close to the edge of the ship, or stood very tall above it.� By the account of Polybius, ships sailed with the corvus upright, so there must have been some way of holding it there, whether by rope tied to the mast, a cage acting as housing, or some other means.� These details can be surmised from surviving accounts, but the full story has been lost to us by the passage of time.�

Fig. 1.� An 18th Century Frenchman�s guess

at the mechanization of the corvus.3

Considering the resources

available on the Italian peninsula, especially near Rome, iron is the most

likely candidate for the massive part of the device that gave the corvus its

name. �The Etruscans in their heyday had

ironworks, so surely something of this technology must have been passed on to

the Romans.� In addition, the color of

iron befits that of a raven better than copper, tin, or a combination of the

two, and one can be sure that a precious metal such as gold or silver was not

used.� Whilst iron may seem the obvious

choice, lacking concrete information we cannot be sure.� It may have been nothing more than a big

sharpened rock.

����������� To

the Phoenicians, naval warfare was an art unto itself, cultivated over

centuries of war in the eastern Mediterranean against a plethora of

enemies.� Their maneuvers and strategies

were so studied and wellpracticed that they laughed at even the thought of the

Romans building a navy.� The Romans were

but another set of barbarians in the western Mediterranean for Carthage to

bring under its sway.� Never did they

consider the remote possibility that Rome might win a victory at sea.�

When, in 260 BC, the Roman

fleet was finally sighted near the coast of Sicily by the Carthaginian

admirals, there was an even greater cause for laughter as each ship carried its

ungainly looking corvus on its deck.�

The laughter turned to amazement when the two fleets met in battle.� Whilst the Carthage battle plan was

masterfully conceived, the Romans completely ignored this and tried to get as

close to the Carthaginian ships as possible to utilitize their ravens.� This was accomplished with deadly

effect:� A Roman ship, drawing close to

a Carthaginian one, would drop the corvus on the deck of the enemy.� The corvus, by virtue of its large mass,

would pierce the deck to the holds below, forming an inextricable bond between

the two ships.� Then, off the Roman deck

onto the Carthaginian by way of the gangplank attached to the corvus, rushed

the surge of legionnaires dressed in full battle gear.� The enemy met was wholly unprepared for such

an onslaught, and was quickly annihilated.�

According to Polybius,

Some of the Carthaginians were cut down, while others surrendered in bewildering terror at the battle in which they found themselves engaged � exactly like a land fight.3

The day was thus squarely won by the Roman with his

corvus.

This first naval victory for

Rome turned the tide of the First Punic War, which Rome would shortly win.

Carthage�s first son, Hannibal, beloved of Baal, would reverse the Roman tactic

in the Second Punic War by besting the legions on land for over a decade before

the unrelenting Romans finally triumphed.�

The third and final meeting of the two would result in the complete

destruction of Carthage, where the Romans went so far as to sow their fields

with salt.� The corvus, though, was

involved in none of this.� However

useful a weapon of naval warfare the corvus was, it was a detriment to the

seaworthiness of vessels carrying it.�

After their unbelievable success, the Roman fleet got caught in a winter

storm off the coast of Sicily and the top-heavy corvus helped to sink most of

the ships.� Roman resources, far

superior to that of Carthage, allowed Rome to build a completely new fleet by

the next year.� Now without the corvus,

they would continue to dominate the seas until the middle ages.

Perhaps one day marine

archaeologists will find a corvus-bearing ship off that fateful Sicilian coast,

but until that day we can only imagine what this ingenious invention that so

artfully defeated the great Phoenician navy of Carthage might have looked

like.��

References:

1. Dodge, Theodore Ayrault, Hannibal: A History

of the Art of War among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of

Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War, (1891).

2.� Edey,

Maitland A., The Emergence of Man: The Sea Traders, (1974).

3.� Thubron,

Colin, The Seafarers: The Ancient Mariners, (1981).